Scotland did not have its own coinage until over a millennium after England. Each time a coinage was established in England, be it during the Iron Age, Roman or Anglo-Saxon periods, Scotland was excluded. This doesn’t mean that some of the English coins didn’t make their way north through trade, rare finds of coins from these early periods have been made in Scotland but it is clear that there wasn’t a need for a more widespread currency until the Early Medieval period. Worthy of mention are the numerous Viking period hoards which have been found scattered along the western coast, reminding us that the Norsemen held the northern and western parts of Scotland for substantial periods, contributing to Scottish culture and character. These hoards represent both trade and plunder, comprising mainly of English coins with European and Eastern pieces occasionally found. Local tradition states that the Vikings were the first to mine silver on the western island of Islay but there has been no evidence of this found to date.

Following the Norman conquest of England many members of Anglo-Saxon aristocracy sought refuge in Scotland and brought with them the knowledge that was necessary to start and maintain a monetary system. Scottish coinage was born in the early 12th Century AD and f or over two centuries it followed a course parallel to that of England, in respect of general design and quality of metal(probably to encourage acceptance and trade between the two kingdoms.)

During the reign of Alexander III (AD1249-1286) at least 18 separate mints were opened, perhaps an attempt to mirror Athelstan’s success in England some 300years earlier. A map showing the location of these mints is shown on the left. His successor, John Baliol (AD 1292-1296)struck coins from just two mints, Berwick and St Andrews in the years leading up AD 1296, when much of Scotland’s territory was lost to the English. After 10turbulent years with no Scottish monarch Robert the Bruce was crowned at Scone in AD 1306. Edinburgh was recaptured from the English in AD 1313 followed by victory over Edward I of England at Bannockburn the following year.

William ‘The Lion’ – Perth Alexander III – Roxburgh

DAVID I (AD 1124-1153)

David was the first Scottish king to issue coinage following the capture of Carlisle by the Scots in AD 1136. Carlisle already had an established mint which had been operated by the English together with silver mines nearby. David’s mother was the Anglo-Saxon Princess Margaret who was the daughter of Edward Aethling. This made David the great grandson of Aethelred II (The Unready) of England. David had already received Cumbria and Lothian from his uncle, King Eadgar in AD 1107 together with the Earldom of Northumberland thus making him an English baron in his own right. Although the Scots under David were defeated by the English at the battle of the Standard, near Northallerton, in AD 1139 the subsequent peace treaty gave David’s son, Prince Henry (AD 1139-1152) the Earldom of Northumberland.

The coinage issued by David I and his son Prince Henry closely copied the Type XV Cross Moline fleury pennies the being issued by Henry I of England and later the Cross Moline (Watford) pennies issued under Stephen. Period A. The main mints initially were in Carlisle and Edinburgh but in the later Periods, B, C and D mints were opened in Roxburgh, Berwick and Perth in Scotland whilst under Prince Henry mints also operated in Corbridge and Bamborough.

David I – Carlisle Mint

The quality of some of these coins were good but others are of poor workmanship with legends often blundered. All coin types of this period are extremely rare and new types are still being discovered.

MALCOLM IV (AD 1153-1165)

Following the death of Prince Henry in AD 1152 and then his father David I the following year, the latter’s grandson, Malcolm IV (AD1153-1165) became king at the age of 12. Little coinage was issued under Malcolm IV and only from the mints in Roxburgh and Berwick. The Cross Fleury and Cross fleury over lozenge types issued are all extremely rare and it is likely that blundered coins in the name of David I continued to be issued during this period. In AD 1157 Northumberland and Cumberland were surrendered to the English whilst several rebellions in Scotland itself between AD1160-1164 were also suppressed.

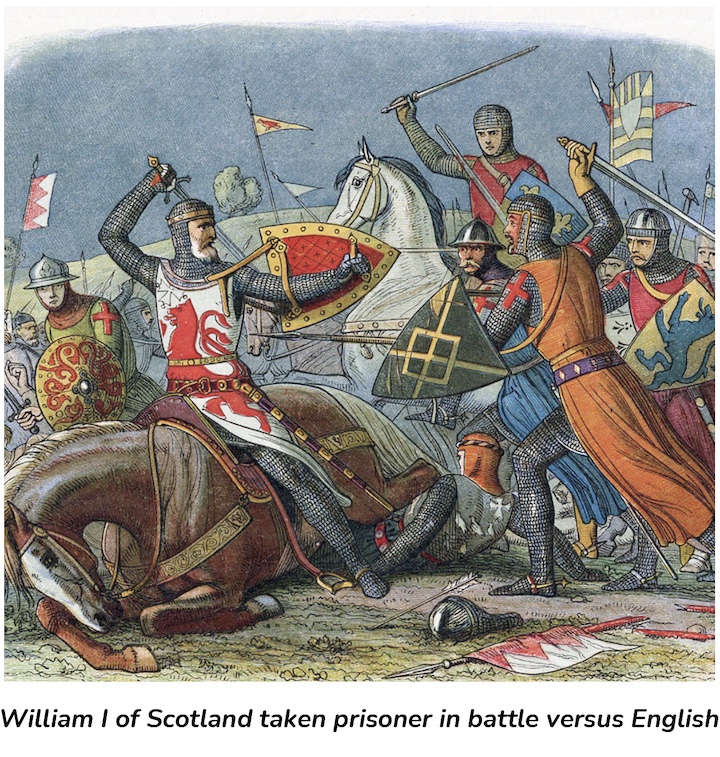

WILLIAM I ‘THE LION’ (AD 1165-1214)

William was the younger brother of Malcolm IV and succeeded the throne in AD 1165. The title ‘the Lion’ was given to him not for his valour but because he replaced the dragon on the arms of Scotland with a lion rampant.

Initially the coinage was similar to that issued under David I with Cross Pattee type pennies being issued from mints in Roxburgh and Berwick. From around AD 1174 until around AD 1195 the more distinct Crescent and Pellet coinage was issued from the mints in Roxburgh and Berwick, also from new mints which were set up in Edinburgh, Perth and Dunfermline. This coinage closely followed the Tealby and Short Cross coinage of Henry II although the facing busts of the English Short Cross coinage was replaced by various profile portraits.

In AD 1174 William was captured by the English. Under the terms of the Treaty of Falaise, William was forced to do homage to Henry II for the whole of Scotland being made to hand over castles in Berwick, Edinburgh and Roxburgh also.

William I – Crescent & Pellet Coinage

William I – Short Cross Coinage, posthumous issue; crude style

Richard ‘the Lionheart’ of England, in need of funds for the Crusades, eventually sold back the independence of Scotland to William for 10,000 merks, equivalent to 1,600,000 silver pence. Most of this sum was likely paid in bullion rather than coin.

During the last part of William’s reign, AD 1195-1214 the Short Cross and stars coinage was issued, some of it posthumously during the reign of his son Alexander II. With this coinage the pellets on the reverse of the contemporary English pennies were replaced by the distinctive stars that continued to be issued during succeeding reigns.

William I – ShortCross Coinage, posthumous issue; fine style

ALEXANDER II (AD 1214-1249)

Alexander II was 16 on the death of his father William ‘the Lion’. He joined the English barons against King John in AD1214. This led to the sacking of Berwick by King Johns forces. With King Johns death there was a reconciliation aided by his first marriage in AD 1221 to Joan, the daughter of King John and sister of Henry III. His second marriage in AD 1239 was to Mary, who was the daughter of Ingelram de Courci, something which surely lost him favour with the English. Much of his reign was turbulent with invasions, insurrections and intrigue. A Norse invasion was repelled in AD 1230 however Alexander II latter died of fever whilst trying to regain the Hebrides from Norway.

For nearly 20 years after the death of William ‘the Lion’ coins were still being struck in his name from the mints in Edinburgh, Roxburgh and Perth. Coins struck in the name of Alexander II are rare. They appear to have been minted mainly in Roxburgh with a few possibly being issued from the Berwick mint.

Coins bearing Alexander’s name were not issued until around AD 1235.

Alexander II – in his own name, c.1235

ALEXANDER III (AD 1249-1286)

Alexander III succeeded his father at the age of seven. His was a prosperous reign which produced the most extensive of all the Scottish medieval coin issues. The short cross coinage minted as the Transitional coinage at the start of the reign gave way to the Great re-coinage which took place during the early AD 1250’s.

Alexander III – First Coinage, Long Cross & Stars

During this ‘First coinage’ a profusion of new mints were set up with a total of 18 operating by AD 1280. Several of these mints were quite small and as a result their identity is still somewhat uncertain. Some of the smaller mints are interlinked through the use of shared obverse dies suggesting that some moneyers coined at more than one mint.

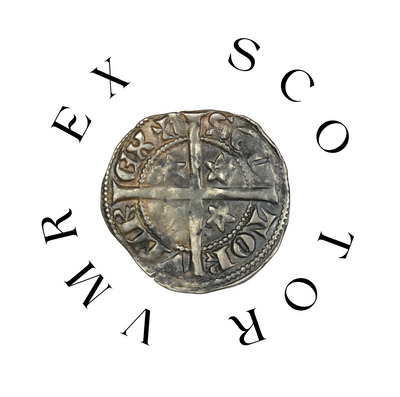

A new style of long cross coinage was introduced around AD 1280, shortly after a similar recoinage had taken place in England. Stars on the reverse of the coins were replaced by pierced mullets and mint names were no longer written although it is generally accepted that mints were still identifiable by counting the number of points on the stars. The reverse legend of these coins reads ‘REX SCOTORVM’, ‘King of Scotland’. This coinage included the introduction of the halfpenny and farthing, again following introductions in England under Edward I.

Alexander III died prematurely through riding his horse over a cliff. With all his children dead his only heir was his granddaughter Margaret who was also the daughter of King Eric II of Norway. Known as the ‘Maid of Norway’ she succeeded to the Scottish throne at the age of three. Her projected marriage to Edward II of England would supposedly lead to a cessation of antagonism between the two countries and possibly to achieve a union.

Unfortunately, Margaret never set foot in Scotland, she died enroute to her kingdom in the Orkneys in AD 1290. No coins were issued bearing her name and it is likely that posthumous coins bearing the name of Alexander continued to be issued during this period.

Farthings & half pennies are rare, as the comparison below shows they were very small and unlikely to have been popular resulting in their quick withdrawal from circulation. The penny on the right is around 20mm diameter, the farthing on the left was just over 10mm.

JOHN BALIOL (AD 1292-1296)

Following the death of Margaret there was an interregnum until John Baliol, a descendant of David I was chosen from amongst thirteen competitors for the Scottish throne. The contestants had agreed to abide by the arbitration of Edward I of England in AD 1291. Coins minted during his reign are similar to those of Alexander III but initially tended to be of coarser workmanship, his first coinage is literally known as the ‘Rough surface issue’. Those of his second coinage were of better quality, referred to as the ‘Smooth surface issue’. The loss of Berwick, Edinburgh, Perth, Roxburgh and Stirling to Edward I in AD1296 led to the abdication of John Baliol. He was taken prisoner by the English and held for three years before being allowed to return to his estates in France where he died in AD 1313. The coinage of John Baliol follows the basic pattern of the previous reign and Berwick appears to have been the main mint, coins were also struck at St Andrews. Halfpennies & farthings were issued but are very rare.

John Baliol – Rough Surface Issue, St Andrews Mint

ROBERT BRUCE (AD 1306-1329)

After 10 turbulent years with no Scottish monarch Robert Bruce was crowned at Scone in AD 1306. Edinburgh was recaptured from the English in AD 1313 followed by victory over Edward I of England at Bannockburn the following year. It was probably not until the recapture of Berwick in AD 1318 that Robert had small numbers of coins struck in his own name. All his coins and in particular his halfpennies and farthings are rare.

The reign of Robert Bruce saw a gradual repossession of the Scottish kingdom partly from the English but also from Scottish rivals. The basic Long Cross coinage introduced by Alexander III was continued during his reign with the issue of pennies, half pennies and farthings. Upon his death in AD 1329 Robert was succeeded by his son who latter reigned as David II.

Robert Bruce – Silver Penny

THE COINS IN DETAIL

Here we take a closer look at the standard legends for coins of the period and describe what they mean.

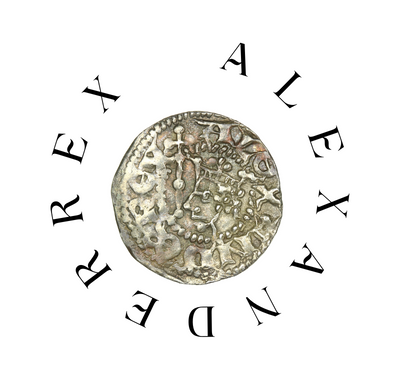

ALEXANDER REX

(Alexander the King)

IOHAN ON BER

(John at Berwick)

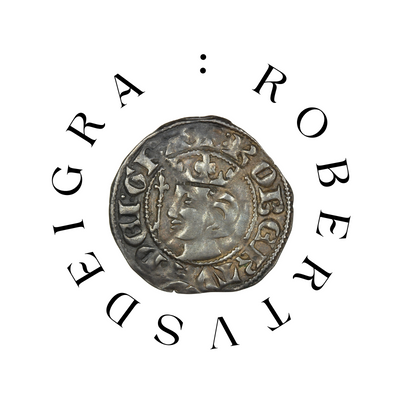

‘ROBERTVS DEI GRA’

(Robert by the grace of God)

‘SCOTORVM REX ’

(King of Scotland)

“The coins featured in this article are part of the Fort collection, a carefully assembled group of Ancient, Anglo-Saxon and Medieval coins collected for their historical importance and condition, sourced from reputable dealers and auction houses around the globe over some 20 years. The comprehensive early Scottish part of this collection in particular enables us to shine a light in to a fascinating period of British history, something which is often the case with coin collecting and why we enjoy the subject so much.” J Philpotts