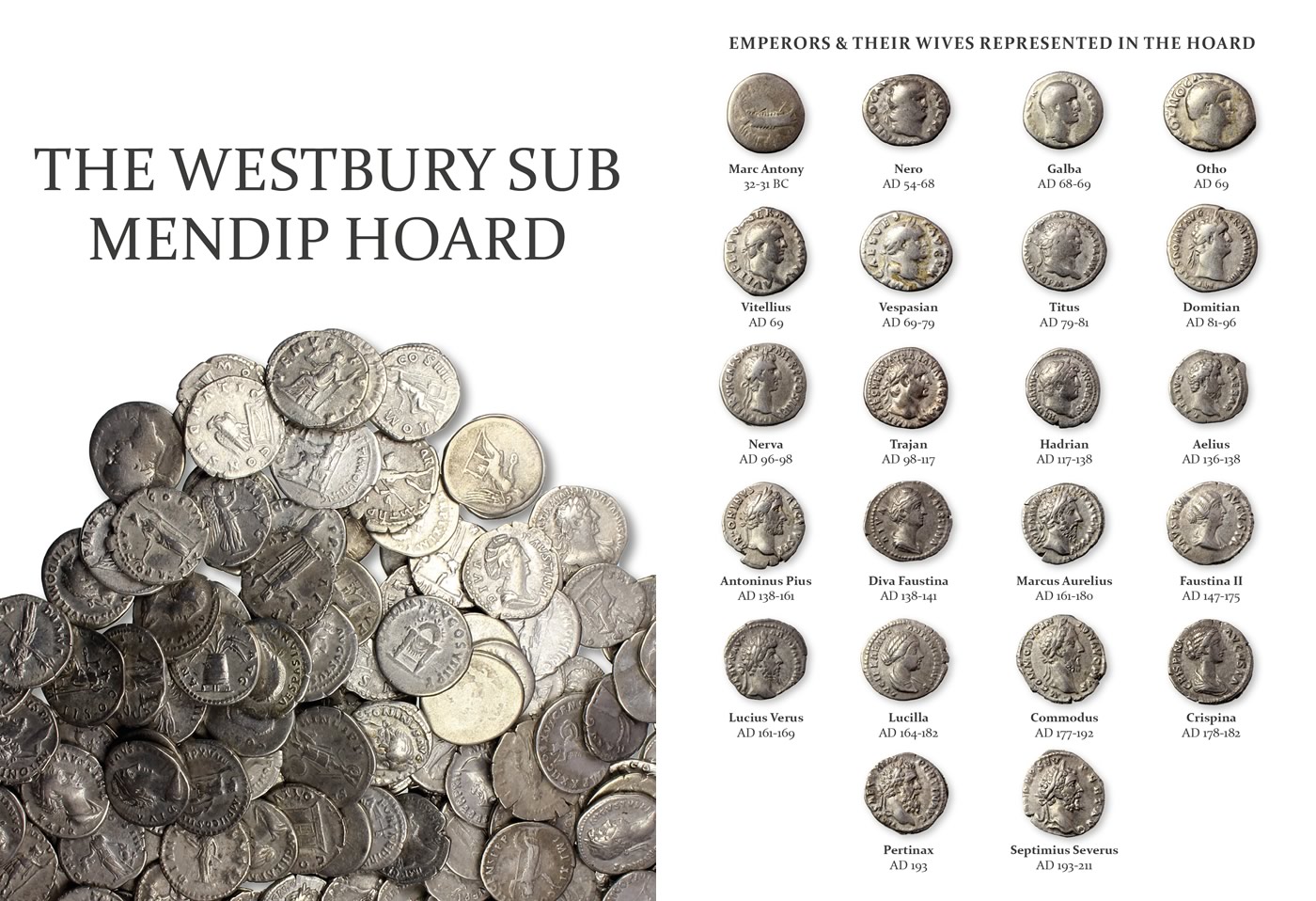

The Beginning, AD 193

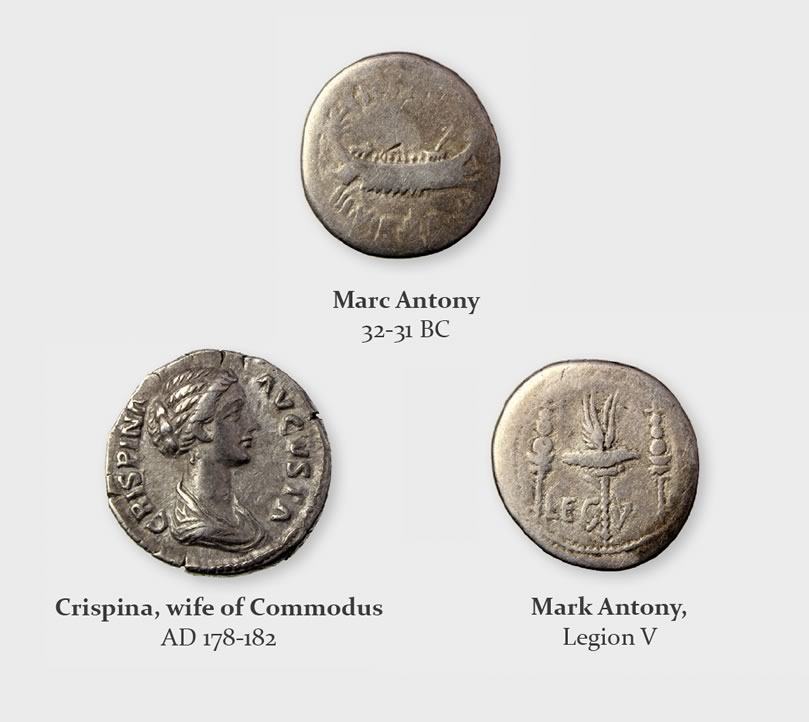

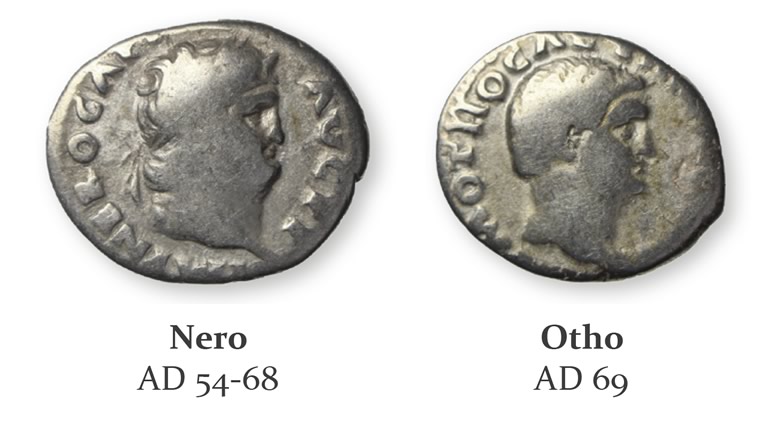

Sometime, during mid to late AD 193 in the South West corner of the Roman province of Britannia, a citizen was compelled to bury his hoard of 188 silver denari, equivalent in value to around £4,500 in modern day currency. This based on the fact that a denarius is thought to have been worth around £25. A Roman soldier would have been paid around 300 denari per year – this doesn’t seem like a lot but remember there were far fewer things to spend your money on back in Roman times! What compelled him to bury the hoard we can only imagine; was it for safe keeping while he headed to market in nearby Wells or had he been asked to head north and help with the trouble caused by the Caledonians near Hadrian’s Wall? Perhaps they were stolen by a mischievous slave who was then caught, sold and could never return to recover his loot. Who knows but, for certain, these coins were not recovered, at least not in Roman times.

The Find, May 2016

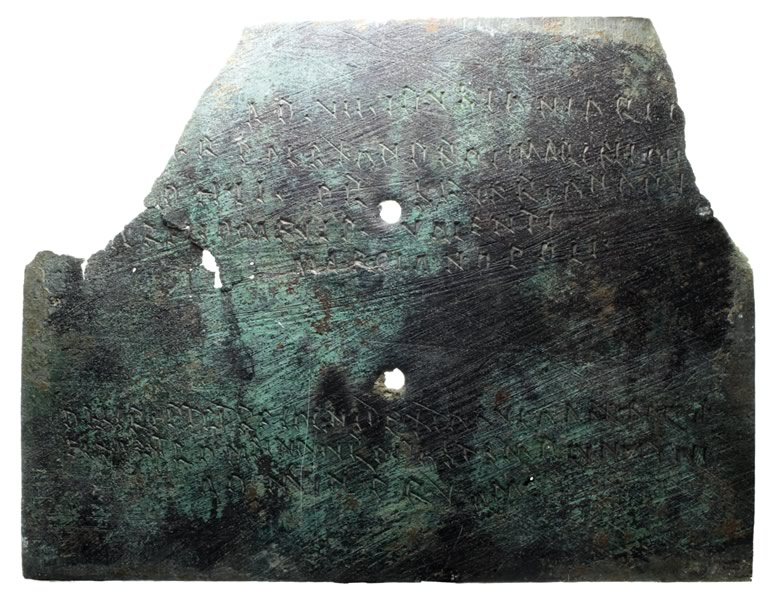

Introducing Daniel Stevenson, Metal Detectorist in AD 2016 searching a small field in Somerset during May where some 1,822 years previously these coins had been buried. The search was arranged by a small club and everyone was excited, due to the history of Roman occupation in the area. The search areas were identified and they headed out into the fields, detectors ready. The first impressive find was a reminder of the significant mining activity which took place in South Western Britain during the Roman period: an impressive lead pig ingot was unearthed. This was a bullion ingot inscribed with the name of the emperors of the time, similar to a modern day gold bar which carries the assay marks. It measured 52cm in length and weighed a whopping 19.3 kilograms! Four similar ingots have previously been found in Somerset suggesting that this is where they were mined during the second century AD.

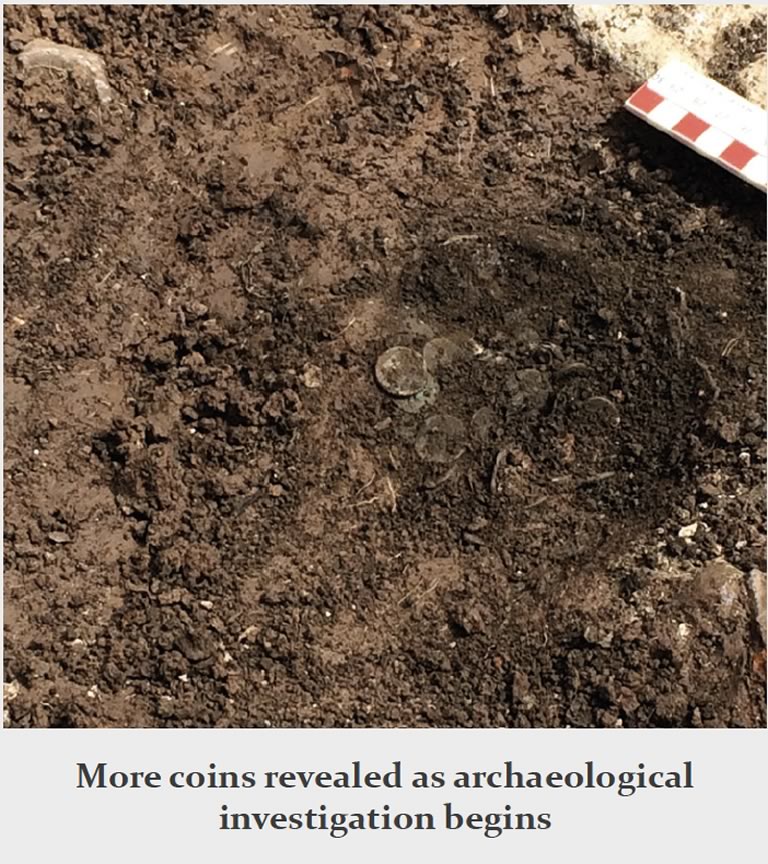

Later in the day Daniel got a faint signal and, upon removing a clod of earth, was greeted with the unmistakable sight of a silver coin. It quickly became apparent that there were more coins in the ground – imagine what must have been running through Daniel’s mind! We’ve all seen the great piles of coins in the British Museum which have been found around England previously, was this the tip of such an iceberg?

Below you can view a video made the day after the initial discovery showing the coins and their excavation.