The Tarrant Gunville Hoard

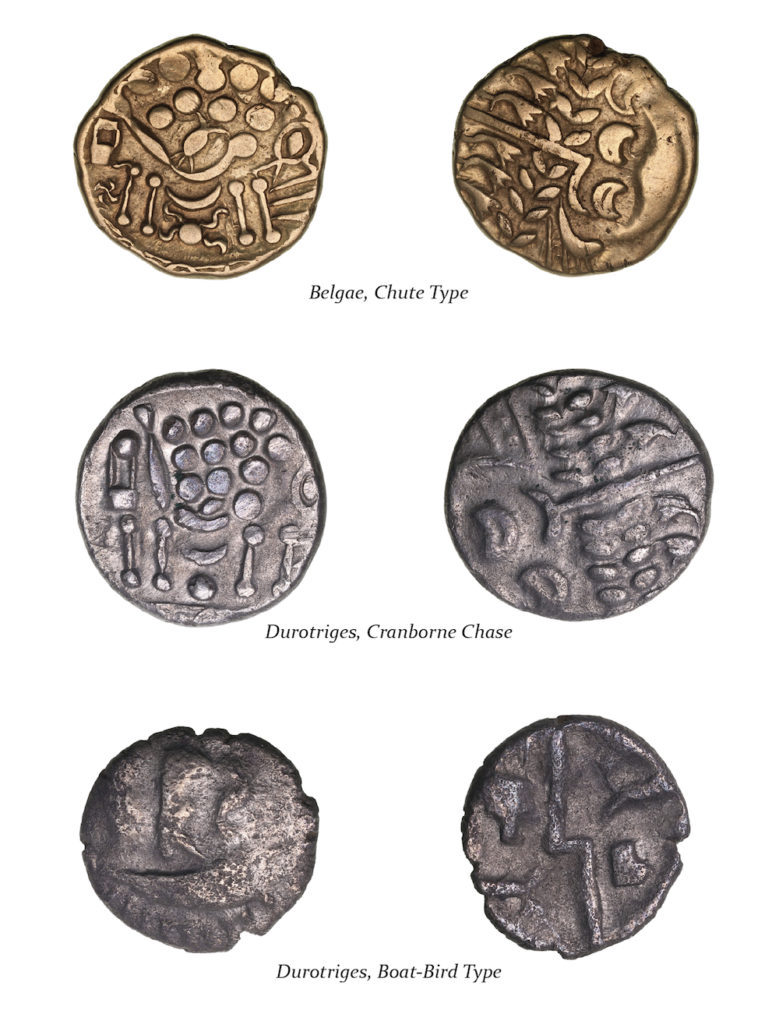

In July of 2022, a metal-detectorist in the east Dorset parish of Tarrant Gunville recovered an important hoard of Iron Age coins. Numbering 31 pieces in total, the hoard (see PAS DOR-00A195, 2022T973) was found in two batches on cultivated land. The initial group of 24 coins was duly reported to the Coroner and Finds Liaison Officer following their discovery, before being handed in to formally progress through the Treasure process. The following year (2023), after the site had been ploughed, a further group of 7 coins were found. With no interest to acquire the hoard forthcoming from either local or national museums, it was subsequently disclaimed and returned to the finder. Having elected to sell the entire hoard en bloc to Silbury, it is now offered here to both collectors and appreciators of the Iron Age series alike.